hnkhwelkhwlnet and TK and TEK #3a

![]() Hnkhwelkhwlnet.pdf.

Hnkhwelkhwlnet.pdf.

The Rainbow. Re-imagine the last time you experienced an arc of richly-varied, vivid color, rising out from the ground, reaching into the sky, and then arching back down into the earth. What were the elements, if you will, “the participants,” and their relationship with each other, which allowed the phenomena you might call a “rainbow” to come into existence? Certainly moisture, the water molecules suspended in the sky, with light from the sun reflecting off those tiny droplets. What else? You, i.e., your physical ability was required, to visually perceive the light interacting with the moisture.

And what else? You again, i.e., your cognitive ability was required to mentally recognize, conceive and conceptualize that the interaction of yourself, with the suspended moisture in the sky, relative to the sun’s light hitting those molecules, was indeed meaningful. You needed a word, an ideational construct. Anything else? How about a certain place, for a certain time. Your rainbow only had existence where these interacting elements aligned in a particular relationship with each other, i.e., you had to be at a place, on a landscape, in a particular angle relative to the light and the moisture. And your rainbow only had existence when these participants come together, aligned if only momentarily, as an unfolding event. The phenomena we call a “rainbow” has existence as a transitory intersection of those participating, anchored to a particular place, interjected by you with a particular construct infused with certain meaning. We interject, have a word, a “concept,” for these interactions that imbues the experience with semantic significance. We have, in essence, a miyp for it.

The focus of hnkhwelkhwlnet is not so much on the participants, as discrete and concrete objects, as it is on their temporal relationships with each other. Would a “rainbow” have existence if any one of these relational participants were missing? The “rainbow” is not reducible to the solitary qualities of its empirical, physical property’s; Aristotelian materialism does not flourish in this reality. The “rainbow” does not have existence autonomous from human participation; Descartes’ Cartesian Dualism does not estrange “body” from “mind” in this reality; no separation of behavioral action from knowledge. The “rainbow” has existence not as a distinct physical object in the sky, nor reducible to its ideational configuration, but as an unfolding event of the many in relationship with each other. The story of the "rainbow" is from Frey and et alia 2014.

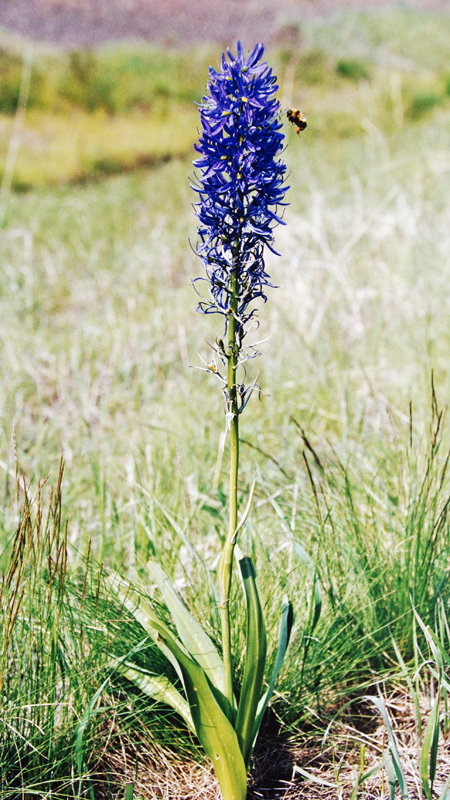

Camas.

Are not both the “raindrops” and “fibrous bulbs of Camassia quamash” made up of similar elemental, constitute physical properties, just simply arranged differently, perhaps most distinguished in that one set of properties is on a much slower temporal scale – a slow growing plant? If a “rainbow” is the result on our interaction and particular relationship with raindrops and sunlight, would it not follow that a “sqha’wlutqhwe” is also the result of our experiential interaction and particular relationship with a relatively hard, fibrous growth, the result of our physical and conceptual interactions with it? Consider that hnkhwelkhwlnet refers to “our ways of life in the world,” i.e., the many participants are a part of a connection with the many others, in a particular place, and not apart from them, separate from that place. For the Schitsu’umsh, this particular physical interaction entails the behavioral acts of prayer, the acts of digging, the acts of cleaning and storing, the acts of sharing the sqha’wlutqhwe’ with those in need, with the elders and children, and the acts of consuming and providing nutrition and health. It entails acts with both physical and spiritual others, with a “brother,” and with the Creator, though the event is not reducible to either the physical or spiritual. The conceptual interaction with the fibrous growth anchors the event with the miyp that guides the behavioral acts and renders the interactions meaningful, though the event is not reducible to the ideational. The entirety of this unfolding event of the many relationships is hnkhwelkhwlnet.

Hnkhwelkhwlnet is phenomena that have existence as a transitory intersection of those participating - human, animal, plant, water, rock, spirit - anchored in place-based oral traditions, the miyp. It is an event made real by those participating, their relationships with each other guided and rendered meaningful by the oral traditions of a specific landscape.

TK and TEK.

Evolving from earlier research and acknowledging variations on the theme, Berkes defines “traditional ecological knowledge as a cumulative body of knowledge, practice , and beliefs, evolving by adaptive processes and handed down through generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment” [author’s italics] (2012:7). It is distinct from the broader more inclusive term “indigenous knowledge,” which is often defined as unique to a given Indigenous community, and within which the TEK’s ecological “land-related” aspects are but one “subset” category. While Berkes notes that among the Australian Aborigines TEK is more than a body of knowledge, it is a “way of life,” the verb-based act of living and doing, the emphasis in the definition and application of TEK refers to the “ways of knowing (knowing, the process), as well as to information (knowledge as the thing known)” (2012:8-9).

In the research protocol for this Sqigwts project, “traditional knowledge” was defined as that “generated, preserved and transmitted in a traditional and intergenerational context; distinctively associated with a tribe which preserves and transmits it between generations; integral to the cultural identity of tribe, which holds the knowledge through a form of custodianship, guardianship, collective ownership, or cultural responsibility.” The foundations for this definition are derived from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), an agency of the United Nations. For additional information, see WIPO. The “traditional knowledge” of this research protocol has general alignment with Berkes’ definition of “indigenous knowledge.”

First, both TEK and TK focus on “knowledge,” on the ways of knowing, while hnkhwelkhwlnet focusing on “ways of living,” with knowing and doing indistinguishably interwoven. The ideational conceptualizing and knowing, the miyp, are not separated from the “living,” from the "doing" 'itsk'u'lm, from the experiential relational connections of the many participants. This would follow the Schitsu'umsh understanding that hnkhwelkhwlnet is devoid of a “mind-body” Cartesian Dualistic premise. When the knowing becomes an isolate, it can too easily and inadvertently be objectified, given a concreteness, as if an “object,” which is inconsistent with transitory character of hnkhwelkhwlnet.

Second, while observing TEK over time, as in the context of climate change, Berkes asserts that it is “evolving by adaptive processes,” it is “constantly evolving” (2012:190). This is also the case for hnkhwelkhwlnet. But the distinction resides in at what level the changes are occurring within the body of knowledge and practice. As will be introduced to you shortly in the 3-D Landscape, hnkhwelkhwlnet provides for the “flesh and muscle” to adjust and adapt to various forms of change, while maintaining its unflinching miyp teachings, retaining its steadfast “bones.” As a tree, its trunk is firmly anchored to the earth, with branches bending with the wind, with branches from all-together different trees grafted onto its trunk, embracing change. Stable, yet dynamic.

And third, given the nature of hnkhwelkhwlnet, even the application of the term “knowledge” should be cautiously considered. While there are numerous definitions of “knowledge,” including the varied postulations emanating out of Western philosophy, it is commonly defined as an understanding of something, based upon facts, information, or skills, which is derived from and acquired through human experience or education, involving perceiving, discovery or learning. Explicit is the proposition that knowledge is generated and created through human experience. When applied to hnkhwelkhwlnet, we would want to also acknowledge that at the heart of Schitsu’umsh knowledge and practice – the miyp, while mediated through human experience, do not ultimately derive from human experience, having originated from the Creator and First/Animal Peoples. And given the scope of hnkhwelkhwlnet, perhaps the term “wisdom,” should also be applied. Wisdom is often defined as a deep understanding that goes beyond knowing, to thicken and extend our understandings, to apply knowledge in all aspects of our lives, private and public, locally and while engaging distant strangers, to address challenges faced by our humanity. Hnkhwelkhwlnet, like wisdom, seeks to take up and tackle the “big questions.”

The constructs of Traditional Knowledge (TK) and Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) offer invaluable insights and should be used in conjunction with a local Indigenous community’s understanding of their ways of knowing and ways of living. A conceptualization of Indigenous knowledge and practice is ultimately that which results from stmi’sm, from being attentive and listening, to build a consensus of the many local Indigenous participants.

Copyright: Coeur d’Alene Tribe and University of Idaho 2015.